CRAYWEED FACTS

Get the lowdown

Crayweed Facts

Crayweed = “Phyllospora comosa” or “P. comosa”

Crayweed was once dominant on reefs in Sydney but disappeared completely from the coastline adjacent to the metropolitan area during the late 1970s and early 1980s (Coleman et al. 2008).

Its disappearance coincided with high volumes of poorly treated sewage waste that was (until the late 1980s and early 1990s) released directly onto Sydney’s beaches and bays (Coleman et al. 2008).

Water quality has improved dramatically since that time, due largely to the construction of deep water sewage outfalls (Scanes & Phillip 1995; Sydney Water Report 2007), but crayweed has failed to recover in Sydney (Coleman et al. 2008).

Crayweed supports a unique component of coastal biodiversity, which is not supported by any other extant seaweed species. Therefore, once it’s lost from an ecosystem, many other organisms and ecosystem services are also lost.

Crayweed supports much higher abundances of abalone (7-10 times) than other seaweed species in the region (e.g. Ecklonia radiata) or barren habitat (Marzinelli et al. 2014).

Crayweed also contributes uniquely to detrital food webs (Bishop et al. 2010), which support recreationally and commercially important fish species, including Bream and Mulloway.

Crayweed has a specific diversity of microbes on its surface, compared to other seaweed species (Campbell et al. 2015).

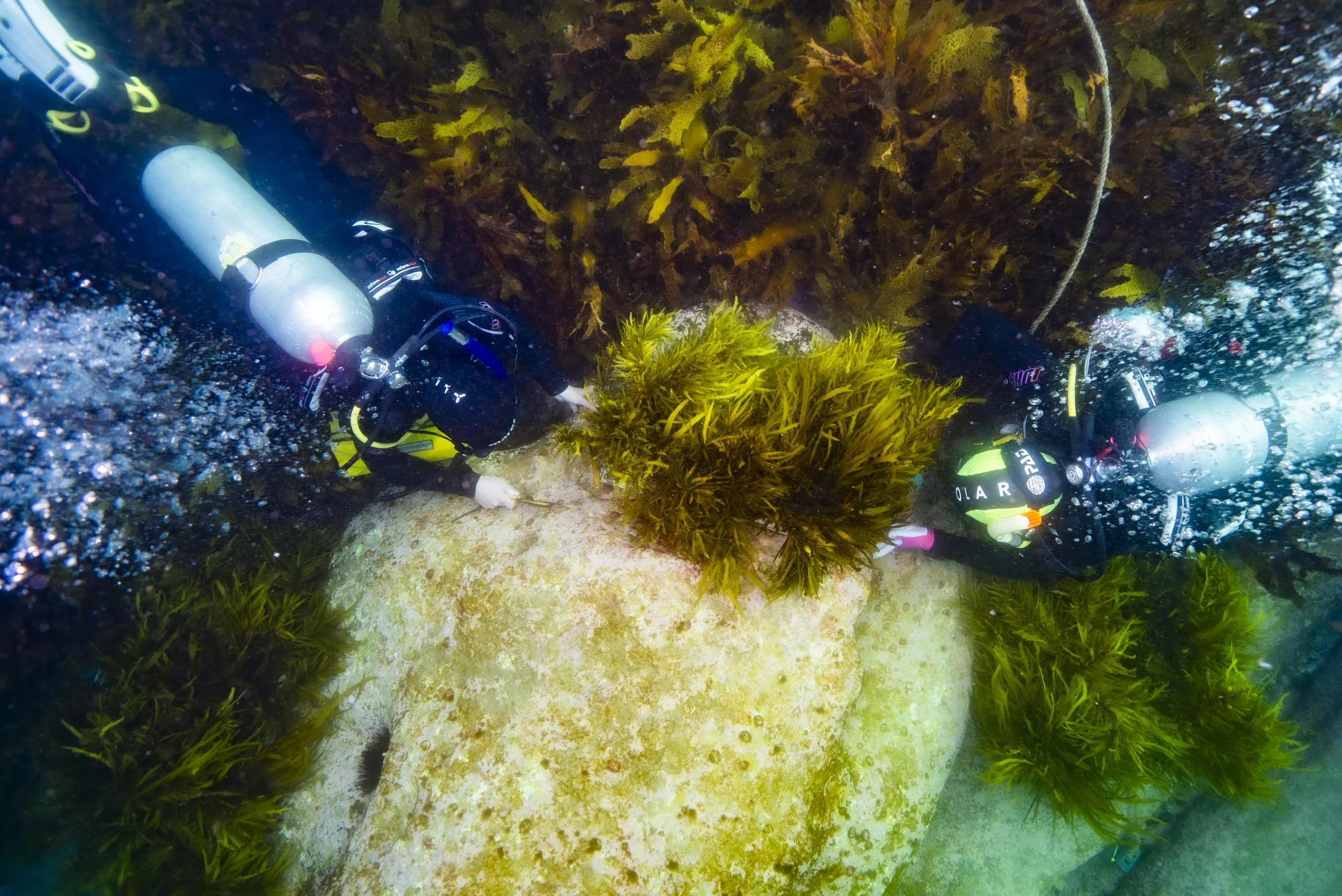

In our first attempt to restore this seaweed (initial experiment run between February 2011 – May 2011 and repeat experiment set-up in August 2011), survival rates of transplanted crayweed were similar to those in undisturbed, remnant populations (~70%; Campbell et al. 2014).

Rates of reproduction and the resulting numbers of babies (“recruits”) were very high – around 100/0.1 m2 (ten times higher), 6 and 12 months after transplantation (Campbell et al. 2014).

By late 2015, none of the originally transplanted, fertile adults remained (through natural loss and mortality). However, many of the ‘babies’ produced by our transplants remain firmly attached to the rock and have now become reproductive adults in their own right. We now find dozens of these new plants at our sites, tens or even hundreds of meters from the originally restored patch, indicating that this method can successfully restore self-sustaining populations of crayweed at places where it was once dominant but has been missing for decades.